|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Cost of NOT Breastfeeding

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

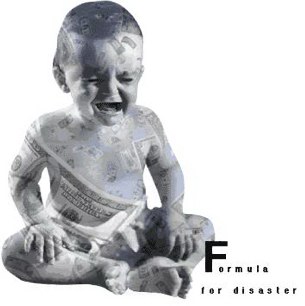

Make an Informed Decision KNOW the Difference between the

BENEFITS of BREASTFEEDING and the RISK of FORMULA

A Word About Infant Formulas

Infant formulas were originally designed to be a medical nutritional tool for babies who are unable to breastfeed due to unfortunate circumstances such as maternal death or illness, inability on the part of the infant to breastfeed due to prematurity, malformation of oral cavity, illness, or in the rare event that a mother had insufficient milk supply. Of course, this was before the time of effective, comfortable breast pumps that could enable a mother to provide her own milk to her infant under most of these types of circumstances. Formula does not fully meet all the nutritional needs or any of the immunity needs of infants, it leaves their immune systems flailing and open to possible disease and infection as well as increases their changes of allergies due to receiving foreign proteins at a time when the baby's gut is still very immature and developing. Only breastmilk is species specific to the human infant and only breastmilk is the perfect food for a human infant.

The American public has bought into the myth that formula is perfectly safe. Does the FDA approve infant formulas before they are marketed? The law does not require that FDA approve infant formulas but instead requires companies to provide certain information to FDA before they market new infant formulas. Manufacturers must provide assurances that they are following good manufacturing practices and quality control procedures and that the formula will allow infants to thrive. If such assurances are not provided, FDA will object to the manufacturer's marketing of the formula; however, the manufacturer may market the new infant formula over FDA's objection. (See Recalls of Infant Formula)

Be informed, make informed decisions! These links are provided to help inform.

Outcome of Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding (with supporting studies)

Artificial Baby Milk (infant formula) and other Baby Food Companies often use deceptive advertising.

HELP REPORT deceptive advertising by logging onto the Federal Trade Commission web site

making a complaint. https://www.ftccomplaintassistant.gov/FTC_Wizard.aspx?Lang=en

BREAST MILK, fed at the breast...FREE

There is no comparison in the health advantages or digestibility of formula to breast milk.

Breastmilk contains 10,000 living cells in every teaspoon.

Formula is dead and contains only some of the nutritional ingredients

of breastmilk, not all, and none of the antibodies and immunities.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all babies be breastfed

exclusively for the first six months and continue for at least the first year or

as long as mother and baby mutually desire.

Artifical Infant Formula Prices

Prices from Publix Supermarkets, Orlando, FL (April 2005)

Formula prices below are based on an average daily consumption of 30 ounces per day.

Formula for Profit : How Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes Undermines the Health of Babies

Cost Benefits of Breastfeeding

Medical costs for breastfed infants were ~ $200 less per child for the first 12 months of life than those for formula-fed infants; extrapolating this to the Healthy People 2000 goal of 50% of infants breastfed could save this HMO up to $140,000 annually. This study included office visits, drug prescriptions and hospitalizations (Hoey and Ware, 1997).

Infant diarrhea in non-breastfed infants costs $291.3 million in annual health care costs Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) costs $225 million in annual health care costs Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus costs from $9.6 to $124.8 million in annual health care costs

Otitis media costs $660 million in annual health care costs.

TOTAL ANNUAL COST OF NOT BREASTFEEDING: $1.186 to $1.301 BILLION

Additionally, formula provided by WIC program to non-breastfeeding mothers costs $2,665,715 annually (Riordan, 1997)

Increasing breastfeeding in Australia could add $3.4 billion to the national food output (equal to an extra 0.7% of the GNP). (Smith, 1997)

Reduction in childhood cancer saves $10 million

Reduction in childhood diarrhea $100 million

Reduction in ear infections $500 million

Reduction in tympanoslomies $500 million

Reduction in juvenile onset diabetes $2.6 billion

Reduction in hospitalization for RSV $225 million

TOTAL CONSERVATIVE ESTIMATE OF COST SAVINGS NATIONALLY FOR ONE YEAR: $4.18 BILLION (Lee, 1997)

Cost savings in disease: $3.689 billion

Cost savings in health expenditures: $3.96 billion

Cost savings in household expenses: $2.835 billion

Breastfeeding Support costs (1 LC/1000; additional training; direct support): $360 million

Cost/benefit ratio of 0.7--over $1 billion would be saved by providing Lactation Consultant support (Labbok, 1995)

Annual reduction in maternal medical at delivery (Philadelphia-based): $91,650. Annual reduction in pre menopausal cancer: $202 million. Annual reduction in domestic violence: $42.5 million (Lee, 1997).

Overall estimated savings of $459-$808 per family enrolled in four social service programs: Medical, WIC, AFDC, Food Stamps. (Tuttle and Dewey 1996)

Overall estimated savings of $112 for the first six months of life per infant enrolled in Medicaid; pharmacy coasts were one-half that incurred by formula-fed infants—based on infants who were breastfed exclusively for a minimum of three months. (Montgomery and Splett 1997)

Overall a minimum of $115 million could be saved/year in Australia by increasing breastfeeding rates to 80% at three months – calculating savings only in otitis media, IDDM, gastrointestinal illness and eczema. (Drane 1997)

SHORT-TERM BENEFITS

Pitocin, usually administered to newly post partum mothers to prevent hemorrhage, costs about $4.49/patient for supplies: ($0.84 18 French angiocath; $1.40 IV tubing; $0.76 saline IV fluid; $0.30 one ampule pitocin; $1.10 syringe). Babies breastfed immediately postpartum make this process unnecessary, saving $4.49/patient X approximately 2 million breastfeeding babies/ year = $8.98 million annually.

LONG TERM BENEFITS

Breast Cancer

Treatment of breast cancer is approximately $30,000 annually/patient. Breastfeeding reduces the incidence of breast cancer. (Lee 1997)

Diabetes

Breastfeeding reduces a diabetic mother's need for insulin and a two-fold reduction or delay in the onset of subsequent diabetes for a gestational diabetic. Treatment of diabetes takes one of every $7 of health care dollars, and costs the US $130 billion annually. This is for direct treatment and does not factor in the high incidence of kidney disease, peripheral vascular disease and blindness which accompany diabetes.

Emotional Stability

Oxytocin, a hormone released each time a mother breastfeeds, decreases blood pressure, stress hormone level and calms the mother. A 38-fold difference in the frequency of domestic violence and sexual abuse was found between the group that breastfed and the group which did not. (Acheston 1995)

Infertility. Breastfed women were 25% less likely to have hyperprolactinemia, galactorrhea and menstrual disturbances according to Dr. Shafig Rahimova. He also feels that males not breastfed are at greater risk of developing genito-urinary difficulties.

Ovarian and Endometrial Cancer

A WHO Collaborative Study found the relative risk of endometrial cancer decreased significantly with increased duration of breastfeeding; women whose lifetime lactation was 72 months or greater, had the greatest protection. Those breastfeeding for less than one year did not accrue this benefit. (Rosenblatt, 1995)

Lactation has a preventative effect on ovarian cancer. The American Cancer Society estimates 26,888 new cases of ovarian cancer will be diagnosed this year. Among women studied, there was a ratio of 1 breastfeeding woman vs. 1.6 non-breastfeeding women who developed ovarian cancer (= a 60% higher risk factor for non-breastfeeding moms)(Gwinn, 1990)

Osteoporosis

Lactating protects women against osteoporosis; not breastfeeding is a risk factor in its development. Bone mineral density decreases during lactation but after weaning showed higher bone mineral density than those who did not breastfeed. A mother's bone mineral density increases with each child breastfed; lumbar spine density increased 1.5% per child breastfed. Thus a decrease in the risk of a fracture of the hip, vertebrae, humerus or pelvis. (Kalwart and Specker 1995; Hreschyshyn 1988)

In 1983 osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures cost an estimated $6.1 billion dollars; an adult white woman who lives to the age of 80 has a 15% lifetime risk of a hip fracture. (Cummings 1985)

Rheumatoid Arthritis

In Norway, 63,090 women with rheumatoid arthritis were followed for 28 years. The total time of lactation was associated with reduced mortality; the protective effects of breastfeeding appear dose related. (Brun 1995)

Weight Loss

During the first year postpartum, lactating women lose an average of 2 kg more than non-breastfeeding women, with no return of weight once weaning occurs. The impact of overweight impacts health by increasing chances of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. (Dewey 1993)

SHORT TERM (UP TO ONE YEAR)

Allergies

Allergy protection is one of the most frequently cited reasons mothers choose to breastfeed. Premature infants are also protected from allergies; breastfed preemies had less than one-third of the allergies, particularly atopic disease, in the first 18 months of life. (Lucas 1990)

There has not been a documented case of anaphylaxis to human milk. (Baylor, 1991; Ellis 1991) Estimated treatment cost of allergy diagnosis and treatment is $400; acute reaction treatment costs about $80-100 per episode. (Hoey at 1996 ILCA Conference)

Anemia

In 1995, one study showed "none of the infants who were exclusively breastfed for 7 months or more....were anemic." (Piscante, 1995)

Communicable Childhood Diseases

Antibody response to oral and parental vaccines is higher in the breastfed infant. Formula-feeding, particularly soy formula, may interfere with the immunization process. (Zoppie 1989; Hahn-Soric 1990)

Death

Breastfeeding protects against sudden death from botulism. In one study, all of the infants who died were not breastfed. (Arnon 1982) Globally, breastfeeding has been identified as one element of protection against SIDS. (Mitchell, 1991) One study identified the risk of SIDS increasing by 1.19 for every month the infant is not breastfed. (McKenna 1995) Breastfed infants are one-fifth to one-third less likely to die of SIDS. SIDS is a leading cause of US infant death, impacting nearly 7,000 families per year. (Goyco 1990)

Diarrhea

Breastfeeding for 13 weeks has been shown to reduce the rate of vomiting and diarrhea by one-third and reduce the rate of hospital admissions from GI diseases. (Howie 1990)

Breastfed infants are protected against salmonellosis; breastfed infants are one-fifth less likely to develop this. (Stigman-Grant 1995) Breastfed babies are also protected from giardiasis. (Nayak 1987)

Gastrointestinal Disease

Children with acute appendicitis are less likely to have been breastfed for a prolonged time. (Piscante 1995) Breastfeeding may reduce the risk of pyloric stenosis. (Habbick, 1989)

Hospitalization

Breastfed infants are less likely to be hospitalized if they become ill and were hospitalized for respiratory infections less than half as much as formula-fed infants. (Chen 1988)

Formula-fed infants are 10-15 times more likely to become hospitalized when ill. (Cunningham 1986) Breastfed babies are half as likely to be hospitalized for RSV infections; in 1993 about 90,000 babies with RSV were admitted to hospitals at a cost of about $450 million. (Riordan, 1997) Breastfeeding reduced re-hospitalizations in very low birth weight babies. (Malloy 1993) In a Honolulu hospital, readmission rates were reduced 90% following the initiation of a lactation program. The drop was seen in dehydration, hyperbilirubinemia and infection. (Lee, 1997)

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Premature infants fed their own mother's milk or banked human milk were one-sixth to one-tenth as likely to develop NEC, which is potentially fatal. The incidence of NEC in breastfed infants is 0.012; in formula-fed infants it is .072. In Australia, one study has calculated that 83% of NEC cases may be attributed to lack of breastfeeding. (Drane 1997)

NEC adds between one and four weeks to the NICU hospital stay of a preemie. At a cost of $2000/day, this translates to $14,000 to $120,000 per infant. (Lee 1997) Even when infants survive NEC, the disease can leave life-long costs via the development of short-gut syndrome and chronic malabsorption syndromes. A Pennsylvania physician has estimated the cost of at-home IV nutritional support treatment for a child with chronic malabsorption to be $50-100,000/year. (Lee 1997)

Otitis Media

Conservative estimates of savings for this disease alone range from one-half to two-thirds of a billion dollars if women were to breastfeed for 4 months. The savings estimate for Ohio if half of the mothers on WIC were to breastfeed was $1 million. (Riordan, 1997) Based on these figures, health care provider agencies could, conservatively, save two-thirds of what it spends to treat otitis media. More than one million tympanoslomies are performed yearly in the US; at a cost of $2 billion. By reducing the ear infections which cause the need for tubes for ear drainage, two-thirds to one billion dollars could be saved.

Respiratory Infections

Breastfeeding protects against respiratory infections, including those caused by rotaviruses and respiratory syncytial viruses. (Grover 1997) Breastfed babies were less than half as likely to be hospitalized with pneumonia or bronchiolitis. (Pisacane 1994)

Breastfed infants had one-fifth the lower respiratory tract infections when compared to formula-fed infants. (Cunningham 1988)

Sepsis

Infants receiving human milk while patients in the intensive care nursery were half as likely to develop sepsis, a reason for increased length of hospital stays and provider expenditure. (El-Mohandes 1997)

Urinary Tract Infections

Breastfeeding protects babies against UTI and subsequent hospitalization. (Pisacane 1992)

LONG TERM EFFECTS OF BREASTFEEDING

Breastfeeding prevents or lessens the severity of the following conditions.

Allergies

Asthma

Childhood Cancer

Diabetes

Gastrointestinal Disease

Heart Disease

Inguinal Hernia

Multiple Sclerosis

Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Publications

Baumslag, Naomi, MD and Dia Michels. Milk, Money and Madness, 1995.

Cunningham, Allan S MD. Breastfeeding, Bottle-feeding and Illness: An Annotated Bibliography 1986. Lactation Resource Center: Nursing Mother' Association of Australia.

Dettwyler, Katherine, PhD and Patricia Stuart-Macadam. Breastfeeding: Biocultural Perspectives, 1995.

Lee, Nikki, RN, MSN, IBCLC, ICCE. Benefits of Breastfeeding and Their Economic Impact: A Report. August, 1977.

Palmer, Gabrielle. The Politics of Breastfeeding, 1993.

Articles

Acheston, L "Family violence and breast-feeding" Arch Fam Med 1995; 4:650-652

Arnon, SS et al. "Protective role of human milk against sudden infant death syndrome" J Pediatr 1982; 100:568-573

Baylor, JG and Bahna SL. "Anaphylaxis to casein hydrolysate formula" J Pediatr 1991; 118:71-73

Brun, JG et al "Breast feeding, other reproductive factors and rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective study" Br J Rheum 1995; 24:542-546

Chen, Y et al. "Artificial feeding and hospitalization in the first 18 months of life" Pediatr 1988; 81:58-62

Cummings, SR et al "Epidemiology of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures" Epidemiol Rev 1985; 7:178-208

Davies, HA et al. "Insulin requirements of women who breast feed" BMJ 1989; 298:1357-1358

Dewey, KG et al "Maternal weight-loss patterns during prolonged lactation" Am J Clin Nutr 1993; 58:162-166

Drane, D "Breastfeeding and formula feeding: a preliminary economic analysis" Breastfeed Rev 1997; 5:7-15

Ellis, MH et al. "Anaphylaxis after ingestion of a recently introduced whey protein formula" J Pediatr 1991; 118:74

El-Mohandes, A et al. "Use of human milk in the intensive care nursery decreases the incidence of nosocomial sepsis" J Perin 1997; 2:130-134

Goyco PG and RC Beckerman. "Sudden Infant Death Syndrome" Curr Prob Pediatr 1990;20:299-346 cited in the National SIDS Resource Center Information Sheet #1

Grimsely, Kirstin Downey. "Companies find a cost-saving formula for working moms".Washington Post Biz: The Workplace July 1, 1997.

Grover, M et al. "Effect of human milk prostaglandins and lactoferrin on respiratory syncytial virus and rotavirus" Acta Paediatr 1997; 86:315-316

Gwinn, ML "Pregnancy, breastfeeding and oral contraceptives and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer" J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43:559-568

Habbick, BJ et al. "Infantile pyloric stenosis: A study of feeding practices and other possible causes" CMAJ 1989; 140:401-404

Hahn-Soric, M et al. "Antibody responses to parenteral and oral vaccines are impaired by conventional low-protein formulas as compared to breast-feeding" Acta Paediatr Scand 1990; 79:1137-1142

Hoey, Christine, RN, IBCLC and Julie Ware MD, IBCLC. "Economic advantages of breast-feeding(sic) in an HMO setting: A pilot study". Am J Man Care 1997; 3:861-65

Howie, PW et al. "Protective effect of breast feeding against infection" BMJ 1990; 300:11-16

Hreschyshyn, MM et al. "Associations of parity, breast-feeding and birth control pills with lumber spine and femoral neck bone densities: Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988; 159:318-322

Kalwart, HJ and Specker BL. "Bone Mineral loss during lactation and recovery after weaning" Obstet Gynecol 1995; 86:26-32

Kjos, SL et al. "The effect of lactation on glucose and lipid metabolism in women with recent gestational diabetes" Obstet Gynecol 1003; 82:451-455

Lucas et al. "Early diet of preterm infants and development of allergic or atopic disease: Randomized prospective study" BJM 1990; 300:387-840

Malloy MH et al. "Predictors of rehospitalization among very low birth weight infants" Clin Res 1993; 41:791(a)

Mitchell, EA et al. "Results from the first year of the New Zealand cot death study" Breastfeeding Rev 1991; 11:106-114 (also NZ Med Journal, 1991; 04:71-76)

Mothering Magazine "Health News" Fall 1997, pp. 44-45

McKenna, JJ and N Bernshaw. "Breastfeeding and infant-parent co-sleeping as adaptive strategies: Are they protective against SIDS?" Breastfeeding: Biocultural Perspectives, chapter 10, pp 265-303.

Montgomery, DL and PL Splett. "Economic benefit of breast-feeding infants enrolled in WIC" Am J Diet Assoc 1997; 97:379-385

Nayak, N et al. "Specific secretory IgA in the milk of giardia lamblia infected and uninfected women" J Infect Dis 1987 155:724-730

Pisacane, A et al. "Breastfeeding and acute appendicitis" BMJ 1995; 310:836-837

Pisacane A et al.. "Breastfeeding and acute lower respiratory infection" Acta Paediatr 1994; 83:714-718

Pisacane, A et al. "Iron status in breastfed infants" J Pediatr 1995; 127:429-431

Rosenblatt, KA et al. "Prolonged lactation and endometrial cancer" Int J Epidemiol 1995; 24:499-503

Riordan, Jan, EdD, RN, FAAN. "The cost of not breastfeeding: A commentary". J Hum Lact 1997; 13(2)93-97

Sigman-Grant, M. "Confirmation of Breastfeeding as a protective factor from salmonellosis in Pennsylvania infants" FASEB J Abstr: Part 1 Vol 9(7) 1995:A183

Smith, Julie. "The economics of breastfeeding" Australian Financial Review 7/24/97.

Tuttle, CR and KG Dewey. "Potential cost savings for Medi-Cal, AFDC, Food Stamps and WIC programs associated with increasing breastfeeding among low-income women in California" Am J Diet Assoc 1996; 96:885-890)

Ware, Julie MD, IBCLC and Christine Hoey, RN, IBCLC. "Revised abstract: economic advantages of breastfeeding is an HMO situation". ABM News and Views 1997; 3(1)3.

Zoppie, G et al. "Response to RIT 4237 oral rotavirus vaccine in human milk, adapted -and soy formula fed infants" Acta Paeditr Scand 1989; 78:759-762.

Presentations

Hoey, Christine, RN, IBCLC. "Cost Analysis of Breastfeeding and the Lactation Consultant within the HMO Setting" Presented at the International Lactation Consultants Association 1996 Conference in Kansas City, MO.

Labbok, Miriam, MD, MPH. "The Real Cost of Not Breastfeeding" Presented at the La Leche League International conference in Washington DC, July 4, 1997. Draft article submitted for journal publication Cost Effectiveness of Breastfeeding in the U.S.: The Forgotten Woman's and Children's Preventive Health Issue published in the conference syllabus, pp 23-32.

Labbok, Miriam, MD, MPH. "Models for Cost Savings Associated with Breastfeeding" presented July 14, 1995, at the International Lactation Consultant Association Conference in Scottsdale, AR. Conference syllabus, pp 23-24.

Webster, Bernie, SRN SCM HVDip. "Medical and Financial Costs Associated with Artificial Infant Feeding" presented August 11, 1997, at the International Lactation Consultant Association Conference in New Orleans, Louisiana. Conference syllabus p. 57 and Handouts.

(The information on this page, covering the “Cost Benefits of Breastfeeding” were compiled,

and contents are copyright ©1997, by Karen Zeretzke, MEd, IBCLC, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.)

From the Los Angeles Times

The White House vs. mother's milk

The Bush administration squelched ads promoting the benefits of breast-feeding.

By Wendy Orent

September 30, 2007

What science the Bush administration chooses to stifle or promote seems to be a matter of politics and economics. According to a recent story in the Washington Post, the multibillion-dollar baby formula industry pressured the Department of Health and Human Services to weaken a 2004 public-service campaign promoting breast-feeding -- and it worked, even though the science supported the other side.

Numerous studies suggest that breast milk protects infants from developing certain illnesses and that formula-feeding increases their health risks.

The ad campaign was designed to drive home that point. Now the health of millions of infants is at risk because mothers don't have the scientific knowledge the ads would have conveyed to make an informed choice between breast- or formula-feeding.

According to the Post, a recent report by an agency within the Health and Human Services Department makes the same point as the canceled ads but has also been downplayed by the government because of pressure from the formula industry.

The original ad campaign was sponsored by the department's Office on Women's Health and developed by the Ad Council, a nonprofit group that produces public-service TV commercials. One spot shows a pregnant woman riding a mechanical bull while a voice-over says, "You wouldn't take such risks while you were pregnant -- why take them afterward? Babies were born to be breast-fed." Another ad features a hypodermic needle lying alongside a nipple-topped insulin bottle -- and states that formula-fed infants are 40% more likely to develop Type 1 diabetes. The ads aimed to shock women into an awareness that the risks of not breast-feeding their infants were real.

According to Gina Ciagne, a former public affairs specialist in the women's health office who worked on the campaign: "Very soft campaigns had always been used for breast-feeding. These weren't resonating. We needed something to break through the clutter."

Formula companies got wind of the ads on the Ad Council's website and immediately tried to kill them. Powerful economic interests were at stake. For Abbott Laboratories, Mead Johnson Nutritionals, Wyeth Nutrition and Nestle Nutrition, feeding babies is big business. For instance, in 2006, according to public filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Abbott Nutrition, a division of Abbort Laboratories and the industry leader, sold more than $1 billion worth of these products in the United States alone.

At the 2004 meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, formula industry lobbyists buttonholed Dr. Carden Johnston, the academy's new president, and persuaded him to write a letter to Tommy G. Thompson, then-secretary of Health and Human Services, protesting the "negative" tone of the pro-breast-feeding ads. "I support the ad campaign being very positive. Breast-feeding should be a nurturing sort of experience; we should not use guilt," Johnston says now.

Johnston's letter outraged Dr. Lawrence M. Gartner, then-head of the academy's committee on breast-feeding. "The formula companies wanted to get the ad campaign killed [because] of the strong financial relationship between the formula companies and the [American Academy of Pediatrics]," he told me.

Johnston's letter had an immediate effect at the Health and Human Services Department, Ciagne says. So did the lobbyists hired by the International Formula Council: Clayton Yeutter and Joseph Levitt. Yeutter, a former secretary of Agriculture, had been instrumental in setting up the Women, Infants and Children program in 1972. Low-income mothers eligible for this food program buy more than half the formula sold in the United States, and the formula industry partly subsidizes it through rebates. The rebate program alone subsidizes about 2 million families.

In his letter to Thompson, Yeutter complained that "the [breast-feeding] ad campaign . . . is clearly inconsistent with the approach taken by the USDA over the past three decades." In order words, the ads threatened the Women, Infants and Children program's heavy dependence on the formula companies.

At the same time, Wanda Jones, the director of the women's health office, recalled that she and others "began to doubt" the science behind the public-service ads. "The science in these frontier areas was really rather immature," she told me.

But how questionable was the science?

Jones concedes that even in 2004, research showed that Type 1, or insulin-dependent, diabetes occurs at significantly lower rates -- the percentage ranges from 19% to 40% -- among breast-fed babies. Because the data on formula-feeding and Type 2 diabetes are more equivocal, Jones says, the ad with the syringe and nipple-topped insulin bottle was dropped. "Most people don't know the difference between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes [which seldom involves insulin injections], so we felt it would be confusing," Jones said.

Although the science supporting a link between childhood leukemia (15% to 19% lower in children who were breast-fed, according to studies) and asthma (27% to 40% lower in breast-fed children) is strong, the ads on these illnesses were also scratched.

Pressure from the formula companies and the American Academy of Pediatrics trumped the science: Instead of nipple-topped syringes and inhalers, new, soft ads featured dandelion puffs and ice cream sundaes vaguely evoking breasts. The entire campaign, shown in only 17 states, quietly expired in 2006.

The report released in April by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, a unit within the Health and Human Services Department, supports the claims made in the original ad campaign -- and then some. It assessed the research designs, methods and results of 9,000 studies, dating from 1966 to May 2006, on the health implications of breast- versus formula-feeding. The report concluded that there is a substantially greater risk of severe lower respiratory (72% higher), intestinal (64% higher) and middle-ear infections (23% to 50% higher) for formula-fed babies. Sudden infant death is 36% more likely among formula-fed babies.

"The problem with the formula companies is that they're marketing a product clearly inferior to breast milk," Gartner said. No formula can compete, nutritionally or immunologically, with something produced by eons of natural selection and tailored to the precise needs of human infants and their mothers. Women who do not breast-feed put their babies at risk.

Sadly, many of these mothers are in the Women, Infants and Children program. By law, according to Kate Houston, a deputy undersecretary in the Agriculture Department, any participant who wants formula must be given it, and almost half of all infants born in the U.S. receive assistance from the food program. For many reasons, not least that work environments are seldom supportive of breast-feeding, most of these mothers choose formula.

"It's really personal choice," said Mardi Mountford, executive vice president of the International Formula Council. "There are lots of different circumstances that factor in. The mom is the one to make the choice."

Mountford also refuses to acknowledge that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality report has any validity. "I don't accept the science," she says flatly.

It's a neat trick. The formula companies and their supporters have deftly reframed the debate. The science is invalid. So the debate isn't about science anymore, it's just about choice, and mothers shouldn't be made to feel guilty about their preferences.

"If a formula-fed child gets leukemia, we don't want the mother to feel guilt over it, on top of everything else," Johnston said.

No such mother should feel guilty. But she should feel angry that she wasn't told, in some clear, graphic and unmistakable way, what the health risks of formula-feeding are. The terrible thing is that our government had the information and for political and economic reasons chose -- and still chooses -- to keep that knowledge to itself.

Wendy Orent is the author of "Plague: The Mysterious Past and Terrifying Future of the World's Most Dangerous Disease."

JUST A SAMPLE OF SOME OF THE RECALLS OF INFANT FORMULA

June, 1993, Class III

PRODUCT: Mead Johnson Nutramigen brand Infant Formula, 20 calories/fluid ounce, in 3 ounce glass nursettes. Recall #F-480-3.

CODE: MME01 expires 1JUL93.

MANUFACTURER: Mead Johnson Nutritionals, Evansville, Indiana.

DISTRIBUTION: Nationwide, Canada.

QUANTITY: 102,048 bottles were distributed.

REASON: The product was contaminated with glass particles.

December, 1993, Class II

PRODUCT: Nursoy Soy Protein, iron fortified infant formula concentrate, in 13-ounce cans. Recall #F-113-4.

CODE: Two line code: AF28A/NOV94 and BG28A/NOV94.

MANUFACTURER: Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, Inc., Mason, Michigan.

DISTRIBUTION: Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin.

QUANTITY 10,250 cases (12 cans per case) were distributed.

REASON: Some cans are contaminated with Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa which poses a mild to moderate hazard to health in the form of gastrointestinal stress to infants and new borns with developing microbial flora.

September, 1996, Class II

PRODUCT: Carnation Follow-up Infant Formula, ready to feed, in 32 fluid ounce cans. Recall #F-176-7.

CODE: Lot numbers: 6192EWFR617 and 6192EWFR618.

MANUFACTURER: Nestle Food Company, Nutritional Products Division, Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

DISTRIBUTION: Nationwide.

QUANTITY: 11,317 cases (6 cans per case) were distributed.

REASON: The product is adulterated because it may have been produced under insanitary conditions whereby it may have been rendered injurious to health. Furthermore, the product appears separated and has been linked with mild gastrointestinal illness.

July, 1993, Class I

PRODUCT: Soylac Powder, Infant Formula, in 14 ounce cans. Recall #F-492-3.

CODE : Recall Extended on June 22, 1993 to include all lots with partial code W5330. NO 94/W5310/923081 (Canadian) and NOV 94/W5330/923082 (US).

MANUFACTURER: Nutricia, Inc., Mt. Vernon, Ohio.

DISTRIBUTION: Nationwide, Canada.

QUANTITY: Unknown.

REASON: The product is contaminated with Salmonella.

September 1996 - Class I

PRODUCT: Alsoy Soy Formula, concentrated liquid infant formula, in 13 ounce cans. Recall #F-718-6.

CODE: 6150EWAC047 Note: Only the portion of the lot with incorrect lids is being recalled. These lids state "DO NOTADD WATER" and are written in English and French.

MANUFACTURER: Nestle Food Company, Nutritional Products Division, Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

DISTRIBUTION: Maryland, Michigan, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia.

QUANTITY: 2,764 cases (12 cans per case) were distributed.

REASON: A portion of this lot of concentrated infant formula was manufactured with lids intended for ready-to-feed formula. The potential exists for a consumer to follow the lid directions (DO NOT ADD WATER) and not properly dilute the formula prior to feeding.

June, 1997 class III

PRODUCT: Isomil brand Soy Protein Infant Formula with Iron. Recall #F-414-7.

CODE: All lot numbers. Product expires in February 1998.

MANUFACTURER: Abbott Laboratories, The Netherlands.

DISTRIBUTION: Ohio.

QUANTITY: 104 cases (6 cans per case) were distributed.

REASON: The infant formula does not contain the labeled amount of inositol, a nutrient required under 21 CFR section 107.100.

September, 1993 Class III

PRODUCT: Infant formulas, special nutritional dietaryformulas, and dried dairy blend foods (93-658-050).

AGAINST Maple Island, Inc., a corporation, and Daniel W.O'Brien and Ronald D. Zirbel, individuals, Stillwater andWanamingo, Minnesota.

CHARGES: The defendants were charged with adulterating their products because they were manufactured, prepared, processed, packaged, and held for sale under insanitaryconditions whereby they may have become contaminated with filth or rendered injurious to health. Defendants were further charged with adulterating products manufactured attheir facilities due to the presence in those products and in the equipment that produced those products, of salmonella bacteria, a poisonous or deleterious substance,which may have rendered them injurious to health.

FILED August 17, 1993, Complaint for Injunction; August20, 1993, Consent Decree of Permanent Injunction; U.S.District Court for the District of Minnesota; Civil #4789; INJ1332.

October, 1994, Class II

PRODUCT: Carnation Good Start Infant Formula Concentrated Liquid in 13 fluid ounce cans. Recall #F-013-5.

CODE: Lot numbers: 4067EWGC447 (U.S.); 4062EWGC443 and 4067EWGC446 (Canada).

MANUFACTURER: Nestle Food Company, Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

DISTRIBUTION: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Utah Washington state, Wisconsin, Canada.

QUANTITY: 16,878 cases were distributed; firm estimates none remains on the market.

REASON: A small number of cans were found to contain non-pathogenic spoilage organisms indicating the product has the remote possibility of being contaminated with other microorganisms.

Sept 22, 1993, Class II

PRODUCT: Isomil Soy Formula with Iron, (infant formula) Concentrated Liquid, in 13 fluid ounce cans. Recall #F-623-3.

CODE: DEC 94 I 77680 RC.

MANUFACTURER: Ross Laboratories, Columbus, Ohio.

DISTRIBUTION: New York.

QUANTITY: 324 cases (24 cans per case) were distributed by Wegmans.

REASON: Product is in cans with peeling can liners.

Breastfeeding is environmentally Friendly to Mother Earth

|

© 2008-2013 Florida Breastfeeding Coalition, Inc.

This Internet site provides information of a general nature and is designed for the purpose of promoting, protecting and supporting breastfeeding.

If you have any concerns about your health or the health of your child,

you should always consult with a physician or other healthcare professional.